|

It’s not a typical day in the office without a parent asking, “Does my child really need glasses?” When working with a patient with 2.00D of myopia, the answer is obvious, but what about when even you’re not sure if you should prescribe or hold off for another year? While there are some guidelines to help us make this decision, we also have our own clinical experience to rely on when making the final call. We’ve included two similar cases that resulted in us taking two different actions and the reasoning behind each decision.

Case #1

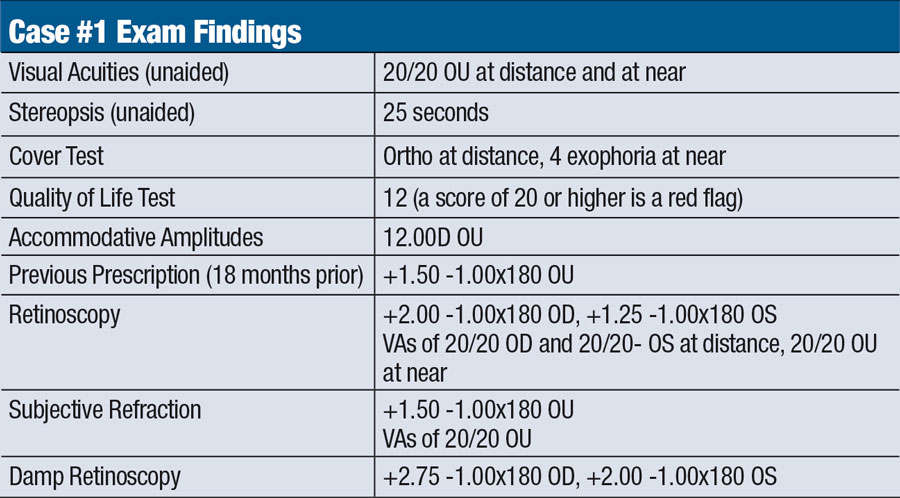

A nine-year-old female came in for her routine exam, stating she had lost her glasses three months prior and had not been seeing well with them. She reported that she actually sees better without them, and her mom said her visual behavior and school performance have not declined since she lost them.

|

The patient did well after receiving her first pair of glasses three years earlier and wore them at school and while doing homework. She was born full-term with no complications and met all developmental milestones. She did not report any problems with squinting or headaches and has been receiving As and Bs in school.

Now, we refer back to the question we hear almost daily and ask ourselves whether this child needs glasses. Every patient has different visual needs, even if they happen to have similar refractive findings, so we must always be thoughtful about how we proceed.

According to our findings, this patient is a high-functioning child who is doing well in and out of school. We agreed that, if this were the patient’s first examination, we would have made the straightforward decision to hold back from prescribing glasses. This is due to the fact that her hyperopia and astigmatism are right at the point when prescribing is recommended, her school performance is not a concern and her uncorrected visual function is within expected levels. Given that this was not her first examination, however, we had to look at all of the facts and discuss with the patient and her parent. Since the patient’s behavior and school performance did not worsen after losing her glasses, a new prescription was not issued. If the patient were to return with near-point complaints later on, a near only would then be considered.

Case #2

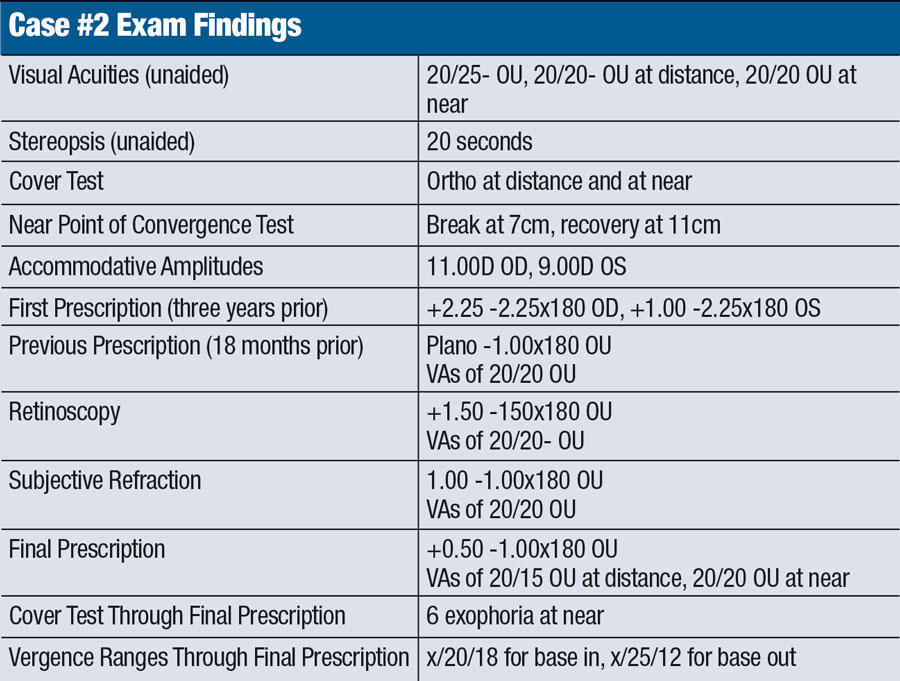

A nine-year-old male presented complaining of slight trouble seeing distant objects, and his mom reported that he squints while reading. She said he has a pair of glasses but often misplaces and has never consistently worn them, even though they were prescribed three years ago. She said his grades in school fluctuate based on how much he can focus while reading.

|

Upon reviewing this case, we can observe that while our findings are somewhat similar to the first, this child presented under different circumstances. He exhibits erratic school performance, poor behavior and suboptimal visual function data. When his acuity is corrected, we can also see an improvement in the cover test and vergence ranges at near, which are close to expected values. Taking all of this information into account, it is obvious that prescribing in this case is less of a question. The patient’s parents were on board as soon as we explained how glasses could positively impact his academics and behavior. Moving forward, we decided to cut 0.50D off the sphere component to allow for acuities similar to, if not better than, those the subjective refraction yielded.

When deciding whether to prescribe glasses, especially for a child, first gather a comprehensive patient history and conduct a complete ocular exam. So much more goes into prescribing than just the numbers.

In both of these cases, we looked to the parents to provide background information. We also relied on the non-acuity-based examination data to guide us in the decision-making process. Without the combination of parental information and visual function testing, it would have been pretty much impossible to see the full picture and decide how to proceed accordingly.