DEWS II: Redefining Dry EyeFollow the links below to read the other articles from our coverage of TFOS DEWS II: A Definitive Decade for Dry Eye What Does “Dry Eye” Mean Today? |

This article covers the following TFOS DEWS II reports:

VIII. Diagnostic Methodology

IX. Management and Therapy

X. Clinical Trial Design.

The heterogeneity of the dry eye population—diverse in both physical characteristics and clinical presentation—adds much complexity to the task of determining the etiology and devising an appropriate treatment plan. The TFOS DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology subcommittee report embraces the idea that evaluating for dryness requires flexibility in approach to accommodate such a varied patient base.

The 2007 DEWS report identified a set of key elements deemed necessary for diagnosis, including symptoms of discomfort, visual disturbance, tear film instability, increased osmolarity and inflammation of the ocular surface. Those elements were expected to be present, at least subclinically, and the aim was to use those clinical findings to narrow the diagnosis into one of two subcategories: evaporative or aqueous deficient. The 2017 DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology recommendations are more nuanced and fluid.

In parallel with this diagnostic refinement, treatment advancements have allowed eye care practitioners to now choose from a wider range of treatment options than 10 years ago. The DEWS II Management and Therapy subcommittee report offers a staged approach to therapy and updated recommendations on treatment methods available for tear insufficiency and lid abnormalities, as well as the ascendant role of anti-inflammatory drugs and lifestyle changes.

GUIDE TO NOTATIONThis supplement summarizes the 10 subcommittee reports that comprise TFOS DEWS II, published in the July 2017 Ocular Surface. The top of each article lists the reports discussed therein. Readers interested in more detail are encouraged to seek out the full text. For easier exploring, key points cite the relevant source by report, paragraph and page number. As you read the ensuing articles, look for TFOS DEWS II citations in this format: [report #, paragraph #, page #] Example: [IV, 2.3, p. 372] |

Diagnostics

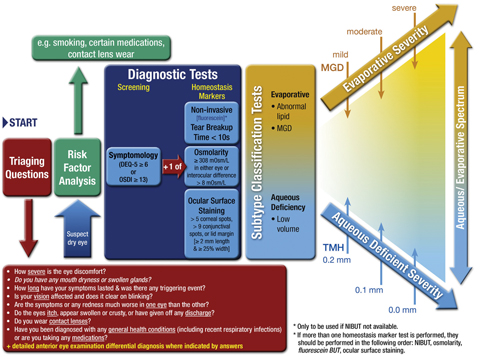

The primary change to the Diagnostic Methodology protocols between the 2007 and 2017 reports is the new publication’s specification of a diagnostic process (Figure 1) rather than circumscribing the approach with a set of mandatory requirements, according to Leslie O’Dell, OD, a member of the TFOS Public Awareness and Education committee. For example, the 2017 report blurs the previously strict division between evaporative dry eye and aqueous deficient dry eye. Instead, it embraces the concept of an evaporative/aqueous deficiency spectrum, which clinicians have long recognized anecdotally.

According to James Wolffsohn, FCOptom, PhD, associate pro-vice chancellor and professor of optometry at the Aston University School of Life and Health Sciences in Birmingham, UK, and chair of the Diagnostic Methodology subcommittee, viewing the two DED categories as discrete conditions does not capture the true spectrum of the condition resulting from the many factors that influence DED.

The report itself advocates a more holistic, patient-centric approach, noting that “any indication that specific signs must be present” to diagnose dry eye “has been removed and an emphasis has been placed on the homeostasis of the tear film. Loss of homeostasis implies the body has lost the ability to maintain equilibrium, resulting in a hyperosmolar, unstable tear film with associated sequelae,” such as increased osmolarity, inflammation, neuropathy and reduced function, according to the report. “Hence, diagnosis requires knowledge of what is considered normal, even though this may vary with patient demographics.” [VIII, 3, p. 545]

Among its many areas of guidance, the report advises practitioners to:

Table 1. Selected Patient Questionnaires for Eliciting Symptoms of Visual Disturbance • Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI)• Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5) • Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Living (IDEEL) • National Eye Institute’s Visual Function Questionnaire (NEI VFQ-25) • Dry Eye-related Quality-of-Life Score (DEQS) • Computer-vision Symptom Scale (CVSS-17) |

• Ask the right questions. The DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report asserts that the first step in a dry eye workup should include gathering a comprehensive patient history via one of the available patient questionnaires (Table 1) to quantify their experience of their condition in a systematic fashion, giving the clinician early signals to pursue. [VIII, 6.2.1, p. 549]

The report reviews all surveys; while each can be a valuable tool, the text states that “the consensus view of the committee was to use the OSDI, due to its strong establishment in the field, or the DEQ-5, due to its short length and discriminative ability.” [VIII, 6.1.1, p. 549] Dr. O’Dell says this recommendation is likely to change how she practices. “For me, the questionnaires are the biggest change,” she says, noting in particular the recommendation to use the DEQ-5, which she previously did not employ. Dr. O’Dell hopes to use it to better diagnose Sjögren’s syndrome, which can make a big impact. “Patients who have Sjögren’s are 44 times more likely to develop lymphoma,” she says.

In addition to questionnaires, the report emphasizes the importance of conducting a patient risk factor analysis by asking about their medications, contact lens wear and tobacco use, among other factors. [VIII, Fig. 5, p .361]

|

Fig. 1. DED DIAGNOSTIC TEST BATTERY. The screening DEQ-5 or OSDI confirms that a patient might have DED and triggers the diagnostic tests of noninvasive break-up time, osmolarity and ocular surface staining with fluorescein and lissamine green. On initial diagnosis, it is important to exclude conditions that can mimic DED with the aid of the triaging questions and to assess the risk factors which may inform management options. Marked symptoms in the absence of clinically observable signs suggest there may be an element of neuropathic pain. Adapted and reprinted from Ocular Surface (2017) 544–579, Wolffsohn JS, Arita R, Chalmers, R, et al. TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report, p. 561, © 2017, with permission from Elsevier. |

• Identify homeostasis markers. Once symptom screening identifies a dry eye suspect, evaluate homeostasis markers. DEWS II encourages doctors to pick at least one from these three categories: tear break-up time (TBUT), hyperosmolarity and ocular surface staining. [VIII, 6.3, p. 551] TBUT is best measured noninvasively, the report indicates, since “fluorescein reduces the stability of the tear film and therefore the measurement may not be an accurate reflection of its status.” [VIII, 6.3.1.2, p. 551] However, the sensitivity and specificity of fluorescein TBUT for patients with Sjögren’s are moderate: 72.2% and 61.6%, respectively. [VIII, 6.3.1.2, p. 581]

Every office has the ability to perform a conventional fluorescein TBUT. Noninvasive TBUT measurements can be performed with a number of devices, including corneal topographers, the Keratograph (Oculus), CA-800 (Topcon), the HD Analyzer (Visiometrics) and interferometers. “Although noninvasive testing is preferred, more sensitive and recommended,” says Paul Karpecki, OD, a TFOS Diagnostic Methodology committee member, “the committee noted that clinicians who do not yet have access to these technologies can default to standard fluorescein TBUT tests to achieve this element of diagnostic testing.”

Doctors may also rely on tear film osmolarity testing, which the Diagnostic Methodology report identifies as having “the highest correlation to disease severity of clinical DED tests, and has been frequently reported as the single best metric (if only one test was used) to diagnose and classify DED.” [VIII, 6.5.1.1, p. 554]

The report also advocates both corneal fluorescein and conjunctival staining to evaluate DED, with a preference for lissamine green over rose bengal, as it is easier to obtain and less toxic, improving patient tolerance. Because staining shows the best correlation to disease severity in severe cases, the report recommends relying on it alone only for severe cases, and looking to the other two options to detect mild and moderate DED. [VIII, 6.5.1.1, p. 554]

• Recognize clinical subtypes. While the subclassifications of evaporative and aqueous deficient dry eye remain in the new classification scheme, the lines between them are now less distinct. Validated by the Diagnostic Methodology report “is what we’ve been seeing—there are a large number of patients in the mixed category, so it’s not just ‘aqueous deficient’ or just ‘evaporative’ anymore,” Dr. O’Dell says. “Newer, more sensitive tests show if patients are predominantly evaporative or predominantly aqueous deficient. My charting is now going to change to say ‘mixed DED, predominately aqueous.’”

• Consider the differentials. Finally, the DEWS II Diagnostic Methodology report discusses the importance of differential diagnosis and recommends triaging questions and procedures to exclude other conditions that may mimic some signs and symptoms of dry eye.

“Because we understand how signs and symptoms do not correlate and that symptoms of dry eye disease can be consistent with numerous other ocular conditions, the committee felt that the addition of this section was vital, which was not present in DEWS I,” Dr. Karpecki says. “For example, there is significant overlap between symptoms of itching and dryness in patients with DED and allergic conjunctivitis. Diagnostic differentiators include tests like osmolarity, corneal staining and even meibomian gland expression. But we also emphasize looking for clinical findings, including systemic ones such as rhinitis, which would indicate allergic conjunctivitis and not dry eye.”

Other conditions that have potential symptoms of dryness, grittiness, burning, stinging and/or redness include conjunctivitis (e.g., allergic, bacterial, GPC and viral, as well as atopic keratoconjunctivitis), infectious diseases (e.g., chlamydia, herpes simplex/zoster), corneal abnormalities (e.g., abrasion, corneal erosion, foreign body and mucous plaques), filamentary and other keratitides (e.g., interstitial) and keratopathies (e.g., neurotrophic and pseudophakic bullous), rheumatological conditions, visual asthenopia and other ocular conditions that mimic dry eye disease (e.g., epithelial basement membrane dystrophy, Salzmann’s nodular degeneration, conjunctivochalasis). [VIII, 9, p. 564–568]

Table 2. DEWS II Staged Management & Treatment RecommendationsStep 1: Step 2: Step 3: Step 4: Adapted and reprinted from Ocular Surface (2017) 580–634, Jones L, Downie LE, Korb D, et al. TFOS DEWS II management and therapy report, p. 615, © 2017, with permission from Elsevier. |

Therapeutics

“If you look at the original DEWS from a decade ago, there were fewer options available and we didn’t have as much latitude” in devising a treatment regimen, says Lyndon Jones, BSc, PhD, Treatment and Management subcommittee chair and director of the Centre for Contact Lens Research at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada. Another key departure, he notes: there was almost no mention of evaporative dry eye in the previous report. “It was almost all focused on aqueous deficient dry eye because that was the level of understanding at the time.” The 2011 TFOS International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction report “made us much more aware of having poor lipid delivery to the tear film and ocular surface,” he observes. In its wake, attention shifted to better understanding this vector of dry eye development.

As a guiding principle for DED treatment, the mantra DEWS II offers is return to homeostasis. “The goal is to screen for and identify dry eye disease, subclassify and target treatment appropriately” to restore homeostasis, notes Dr. Jones. Adds Dr. Karpecki, “it is critically important to follow-up to improve patient outcomes.”

The data pertaining to interventions have been exhaustively researched over the last decade. “The most significant challenge we had as a group was the enormous explosion of studies in our areas to consider compared to the TFOS DEWS original report,” says Dr. Jones. “The original management and therapy report had 185 references, and this one has more than a thousand.”

The 2017 Management and Therapy report presents a hierarchy of treatment modalities, but moved away from a ‘grade’ system used in 2007 and into a ‘step’ approach (Table 2) because, Dr. Jones says, grades suggest that the patient needs to exhibit changes before being moved to a new class of treatments. Doctors should consider earlier detection and treatment for optimal patient outcomes, and also should consider it acceptable to combine treatment approaches found across subclassifications (i.e., aqueous deficient and evaporative DED).

“The more severe the DED is, the more likely you are to climb the management steps,” explains Dr. Jones of the treatment/ management steps listed, which range in order of severity from 1 to 4. “Don’t be concerned about using Step 1 items and adding something from Step 2,” he advises. “They can be used concurrently.”

Key areas to address clinically include:

• Tear insufficiency. Aqueous deficient patients are typically treated using one of three methods: tear replacement, conservation or stimulation. A plethora of replacement options are reviewed in the DEWS II report; however, it reads, “these products do not target the underlying pathophysiology of DED.” [IX, 2.1, p 583] Nonetheless, the report provides updates on the research into the myriad palliative therapies such as osmotic agents. An alternative therapy often used in more moderate to severe DED is autologous serum, considered a tear replacement with potential restorative effects. Tear conservation via punctal occlusion techniques, when combined with other treatment methods, can provide symptomatic improvement, but the evidence remains limited. Finally, the section on stimulation techniques includes a look at lipid stimulators, such as insulin-like growth factor 1, and the new category of nasal neurostimulation.

• Lid abnormalities and hygiene. Blepharitis, bacterial overcolonization, Demodex infestation, MGD and incomplete blinks can all predispose a patient to dry eye. As the Management and Therapy report describes, with “no universally accepted guidelines for lid cleansing” available, patients may feel confused. [IX, 3.1.1, p. 593] However, a whole marketplace of remedies, including warm compress systems and physical treatments, attempt to combat the deleterious effects of lid abnormalities. [IX, 3.1.1, p. 593] Since compliance is typically low with warm compresses [IX, 3.2.2, p. 594], a cottage industry of at-home devices has emerged, such as moist heat eye masks. Additionally, treatments such a meibomian gland expression, intense pulsed-light therapy and LipiFlow (TearScience) all seek to better serve these patients.

• The role of anti-inflammatories. While anti-inflammatory agents such as corticosteroids are effective for short-term use, two in particular are expressly designed and tested for dry eye: Xiidra (lifitegrast, Shire) and Restasis (cyclosporine, Allergan). While these agents are effective, they must be used appropriately as part of a treatment plan that addresses all aspects of DED. For instance, Dr. O’Dell says, “in a patient whose presentation is predominantly evaporative in nature, there might also be inflammation present on the surface triggering hyperosmolarity.” Such a patient would benefit from an anti-inflammatory agent to improve the ocular surface status combined with meibomian and eyelid interventions that seek to restore proper function, she notes. Tear osmolarity, as a biomarker of DED, can help gauge the response to anti-inflammatory treatment.

Dr. Jones concurs on the wisdom of using anti-inflammatory and lid hygiene therapies together. The Management and Therapy report offers that precise recommendation. Dr. Karpecki, who served on the Diagnostic Methodology committee, feels the management recommendations for patients with an evaporative dry eye component include managing lid hygiene, inflammation, meibomian gland obstruction and the tear film in concert.

An Eye to the Future

The TFOS DEWS II publication is a definitive advance in the understanding of DED, like the original 2007 DEWS before it and the TFOS MGD International Workshop, which itself brought to the forefront a greater understanding of evaporative dry eye and the role of lipids in the disease process.

As investigators look to the future, Dr. Jones suggests greater attention to biomarker research could reveal the next breakthrough in understanding and taming this complex, multifactorial disease. “What’s happening on a cellular level of a damaged ocular surface—that’s really interesting,” he says about the frontiers ahead.

While the research world prepares for that radical shift, clinicians can begin to institute a sea change of their own. “I think optometrists should get onto the concept of preventative care, as dentists do,” explains Dr. Jones. “Practitioners generally are not very good at trying to talk to patients about the ocular equivalent of flossing your teeth. If patients were managed earlier and we talked about ocular surface hygiene and moved toward managing homeostasis, maybe we could prevent some from progressing to the more intractable stages of dry eye.”

The report’s tenth and final report, Clinical Trial Design, aims to raise the bar. “What really shocked us was how little high-level evidence there is to support many of the things we do or we prescribe on a day-to-day basis,” Dr. Jones noted at the DEWS II ARVO session. The recommendations the Clinical Trial Design report puts forth are targeted at eliminating what the authors refer to as “vagaries of dry eye disease” that were previously complicating clinical trials. [X, 3.1, p. 636] They endorse a prospective, randomized, doubled-masked, placebo- or vehicle-controlled, parallel-group approach. [X, 3.1, p. 636] With an evidence-based foundation for the eye care community’s current protocols and greater rigor brought to study design, the future looks bright.

Five Ways to apply TFOS DEWS II to your practice todayBy Kelly K. Nichols, OD, MPH, PhD, co-chair of the Definition and Classification committee and Dean of the UAB School of Optometry and Paul M. Karpecki, OD, TFOS Diagnostic Methodology committee member and Clinical Director of Advanced Ocular Surface Disease, Kentucky Eye Institute Have you ever had the feeling you were right on the edge of a defining moment? A game-changer? It does not happen often, but we sit up and pay attention when it does. Recently, we have seen a flood of efforts in the arena of dry eye disease—clinicians starting dry eye-specific clinics, patients asking for treatments, and lectures and workshops focused on dry eye, to name just a few. But what if you are starting from scratch—how can you get there? We can show you how. “The TFOS DEWS II report is the singular most informative dry eye document from the last 10 years—it sums up everything we currently know and the direction we need to go,” says Dr. Karpecki. Adds Dr. Nichols, “this report is less about the sheer volume of the information and more about the knowledge and forward-looking statements—it is what we do with this document as clinicians and scientists that will really make a difference.” For the last 2.5 years, we have both been part of this amazing process, and our collective advice in summarizing the reports is as follows: 1. Ask the right questions. Whether you or your staff administer a dry eye survey, the DEQ, OSDI or ask triaging questions, consistency in symptom assessment will aid screening and diagnosis. 2. Use screening tests. Every practice can perform two of the three recommended screening tests: TBUT, osmolarity and corneal staining. Make the most of your screening process. 3. Determine predominant subtype (aqueous deficient, evaporative). The right dry eye subclassification will guide treatment—and, don’t forget, both can occur simultaneously. 4. Target your management plan. With many options, combined therapy targeting both subtypes will be most effective. 5. Manage expectations. You and your patient are in this for the long haul. An ounce of prevention may avoid a lifetime of suffering, and optometrists are poised to take charge. At Review of Optometry, we are honored to have presented this DEWS II summary to you. Use it well and your dry eye patients will thank you. |