|

Q:

I recently attended a lecture where the presenter mentioned the potential benefit of using a fluoroquinolone when prophylaxis is needed to ward off bacterial infection in a patient with epithelial herpes simplex virus (HSV). I’m not sure what the rationale is here. Is there any research available on this?

A:

“While I’m not familiar with any specific research tying fluoroquinolone prophylaxis into the treatment of HSV keratitis, microbial superinfection is an infrequently encountered, but well-known, consequence of herpetic disease and falls under the clinical spectrum of ‘metaherpetic disease,’” says Aaron Bronner, OD, of Pacific Cataract and Laser Institute.

The terminology used to describe this scenario might be in need of an update, however, notes Dr. Bronner. “Metaherpetic disease is a somewhat dated descriptor of things that aren’t directly HSV-related corneal infections or inflammations, but are still consequences of the previous viral activity.” For these patients, prophylactic antimicrobial treatment could be helpful, he says.

|

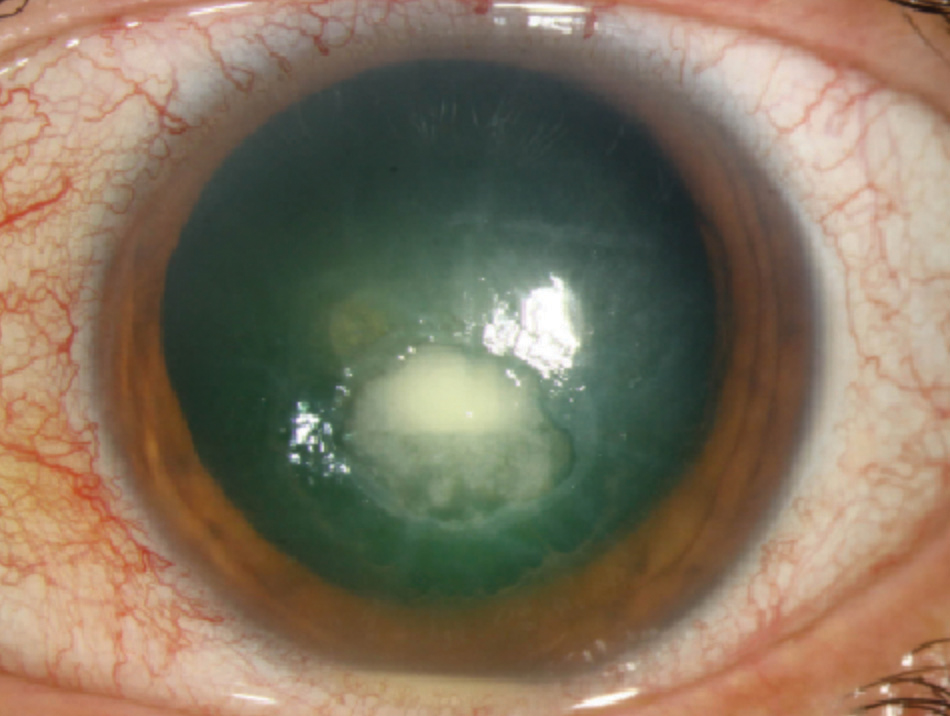

| By implementing prophylactic antimicrobial treatment, practitioners may be able to protect patients from bacterial superinfection, shown here. Photo: Christine W. Sindt, OD |

Why Prophylaxis?

According to Dr. Bronner, the most common metaherpetic finding is neurotrophic keratitis. Metaherpetic microbial superinfection, on the other hand, is “less commonly seen but more acutely sight threatening.”

Here, the mechanism is much like that of any opportunistic infection: “A breach in the corneal epithelium allows opportunistic microbial infection of the cornea, most typically with a member of the normal periocular flora,” says Dr. Bronner. This means that the herpetic infection is only important in two ways in the setting of superinfection:

It provides the break in the epithelium that opens the door to microbial infection, either via a dendritic ulceration or through creation of a neurotrophic lesion.

An early microbial lesion in an eye with previous herpetic activity can be easily misdiagnosed as being herpetic early in its course, which allows the actual etiology to remain untreated, leading to worse outcomes.

“Therefore, prophylaxis against microbial infection has good clinical rationale,” says Dr. Bronner. “That said, for most dendritic ulcers, I don’t routinely add prophylaxis unless the lid margins look unhealthy or the epithelium is slow to heal.” Dr. Bronner does always add prophylaxis in cases of neurotrophic ulcers, however, since these lesions can epithelialize much more slowly, increasing the likelihood of superinfection.

Cover Your Bases

If you are considering prophylactic antimicrobial treatment, be sure to check your patient’s history first. “Any time you are adding antimicrobial prophylaxis, I think it’s wise to ask the patient about a history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA),” Dr. Bronner says. “If they are carriers or have a previous history of MRSA infection, you may need to adjust the prophylactic agent to cover for this.”