|

Retinal artery occlusion (RAO), characterized by acute vision loss due to an arterial blockage, is considered an ocular emergency, as permanent vision loss will ensue in many cases. The blockage manifests as inner retinal swelling associated with a cherry-red spot. In addition, attenuated arterioles, optic nerve atrophy, arterial segmentation (‘box-carring’) and the presence of an arterial embolus may be noted.

Since retinal emboli are the most common cause, conventional therapies focus on vasodilation in hopes of dislodging the associated embolus. Anecdotal therapy modalities used in our office include hyperbaric chamber, paracentesis, antihypertensive medications, ocular massage and transluminal YAG laser embolysis. Although a few of these measures show anecdotal success, given the limited timeline for retinal reperfusion, the prognosis is often grim.

The key to management is the prevention of secondary complications. Thus, traditional evaluation includes testing blood pressure, fasting glucose/HbA1c, fasting lipids, carotid ultrasound, complete blood count with differentials and echocardiography. Because giant cell arteritis may play a role in elderly patients, clinicians should also evaluate erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein and platelet count in any patient older than age 60. Younger patients should have a hypercoagulable and vasculitis workup as well.

|

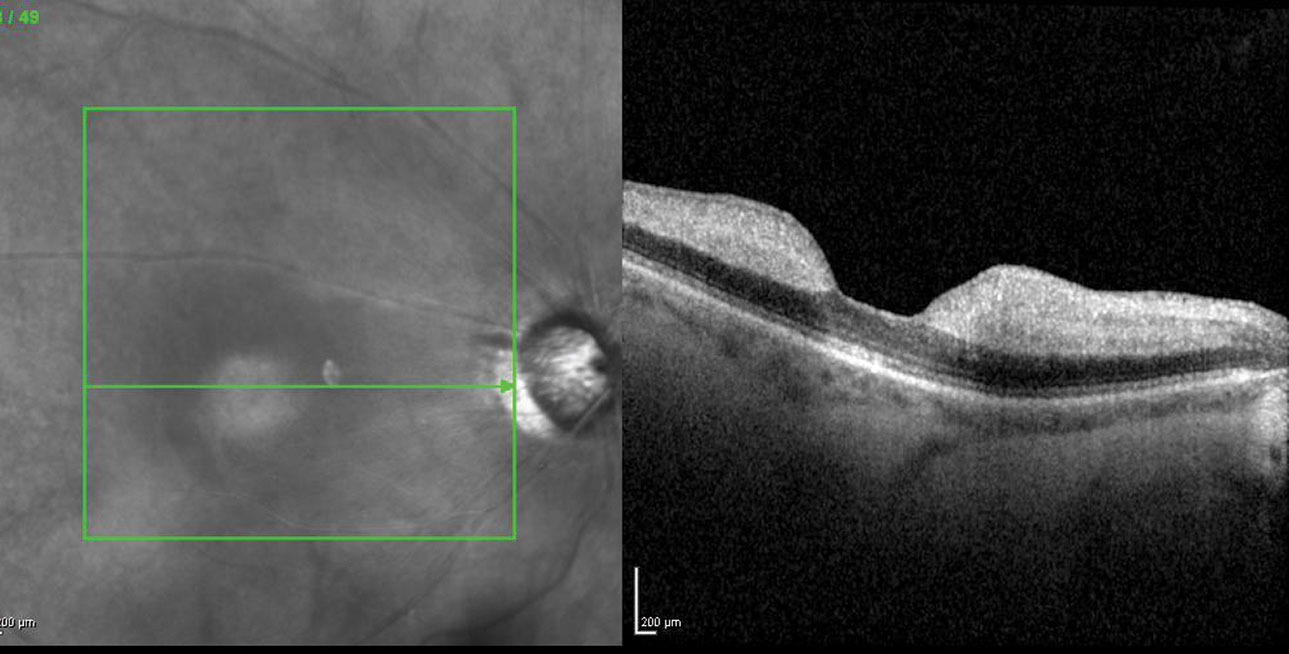

| Fig. 1. OCT is an invaluable diagnostic tool to assess possible retinal thickening, as seen here in another acute CRAO patient. Photo: Jay M. Haynie, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Too Little, Too Late

Case by Drs. Shechtman and Lara

A 72-year-old Caribbean male was referred for evaluation of severe painless acute vision loss of the right eye. Although the patient was initially referred as a STAT consult by a local ophthalmologist, he did not present to our clinic until two weeks later because he had been hospitalized for a stroke shortly after the onset of vision loss.

His best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/400 in the right eye with an associated afferent pupillary defect. Dilated examination revealed a mottled retina, attenuated arterioles and optic atrophy of right eye. Evaluation of his optical coherence tomography (OCT) scans obtained at the initial ophthalmology consult demonstrated inner retinal thickening with associated shadowing of the underlying outer retinal layers. The patient was advised to continue follow-up with his primary care physician and cardiologist and scheduled for a follow-up in four weeks.

Is RAO Akin to Ischemic Stroke?

This case brings to light the realization that RAO and stroke share a common pathophysiological mechanism associated with thromboembolism; they also have similar risk factors. Although the most common cause of RAO stems from an embolic event, other etiologies can stem from thrombosis, spasms, vasculitis or trauma. Confounding risk factors include diabetes, hypertension, hypercoagulability factors and cardiac or carotid disease.

Recent studies suggest RAO is linked to an increased incidence of stroke and mortality-associated complications, considering as many as 25% of patients with an RAO have concurrent brain infarction. Even silent brain infarctions bear a high risk for future stroke, and patients with RAO have more than double the chances of developing subsequent strokes. The magnitude of such strokes is often higher in younger patients, while the increased risk of multiple strokes is often higher among older patients. Researchers suspect the risk of stroke dramatically increases within the first week after the RAO and remains a possibility a month following the event.

In our practice, it is standard of care to immediately refer any patient with an acute RAO to an emergency department with a stroke center with an order for a neuro consult and a diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging.

Additionally, because transient ischemic attack (TIA)/atrial fibrillation (AF) and retinal emboli share the same cause and mechanism as a cerebral ischemia, we customarily employ the same management protocol for patients presenting with TIA/AF and retinal emboli.

Time is of the Essence

Commentary by Dr. Haynie

I concur regarding the management of a patient with an RAO; however, it should be noted that irreversible vision loss from an acute RAO is often permanent after 90 to 120 minutes from the onset of visual symptoms. Unfortunately, many patients do not present to the clinic in time.

In my practice, our MDs will consider an anterior chamber paracentesis to rapidly lower the intraocular pressure, resulting in vasodilation and potential dislodging of the embolism if the symptoms are less than 24 hours old and the patient has a central RAO. If the embolism is in a branch retinal artery, such a procedure is rarely done, as these patients tend to have, and keep, intact central vision.

Regardless, it is important to attempt to lower the intraocular pressure in the office through digital ocular massage, instillation of topical and oral hypotensive agents, breathing into a paper bag and similar interventions if the symptoms are within 90 to 120 minutes. Patients need access to ophthalmology for a consult if management is not readily available and your state license does not permit you to perform a surgical procedure such as an anterior chamber paracentesis.

I also concur on the referral for appropriate diagnostic studies, keeping in mind that time may be of the essence, as the risk of a secondary event (i.e., cerebral stroke) is much higher in patients with a primary RAO. I will generate a summary and urgent referral for the patient and send them directly from my office to the emergency department in the hopes that this urgent request will expedite the ancillary testing and assessment of associated risk factors that may be amenable to treatment, ultimately reducing the morbidity of embolic complications.