|

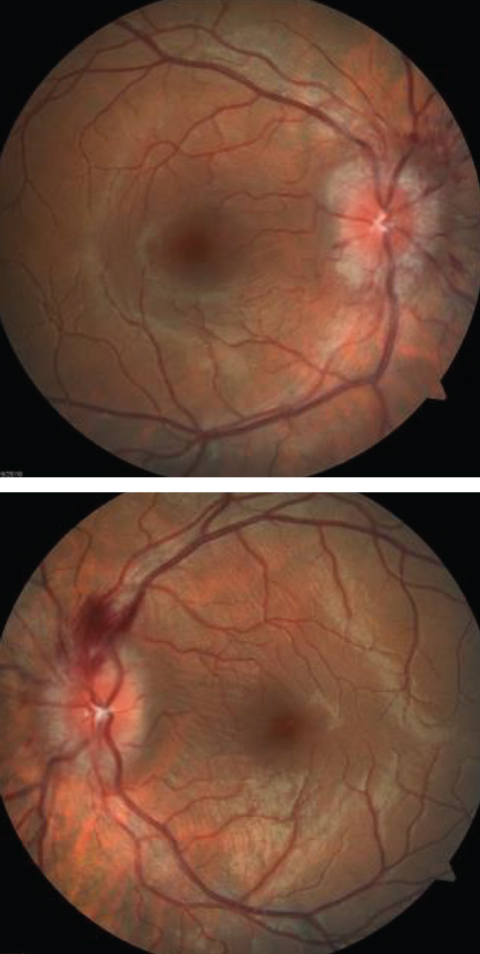

Imagine this scenario: A new patient presents to your office with a chief complaint of headaches. She reports they occur multiple times per week and occasionally wake her from sleep. You perform a comprehensive ocular health examination and a dilated fundus exam reveals the findings pictured.

This patient portrays the telltale signs of papilledema. This neuro-ophthalmic condition is characterized by optic disc edema in the presence of increased intracranial pressure (ICP), which occurs secondary to a disruption in the balance of blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain tissue in the cranium. An increase in volume in any of these cranial components can raise ICP. This can subsequently cause a disruption of prelaminar axoplasmic flow into the optic nerves and result in optic disc edema.1

This article reviews the differential diagnosis, necessary work-up and treatment options for cases of papilledema.

Presentation

Papilledema may be accompanied by visual and neurologic symptoms. One of the most commonly reported symptoms among papilledema patients is headache. These headaches are typically variable and may be severe enough to wake the patient from sleep.1 In addition to headaches, papilledema patients may report symptoms of nausea and vomiting. Increased ICP can cause blurred vision and transient visual disturbances, which worsen with postural change.2 Patients may also report a pulsatile tinnitus or hearing a “whooshing” sound, specifically when lying down.2 Furthermore, papilledema may cause diplopia, which is often due to compression and subsequent paresis of the abducens nerve. Often, however, papilledema patients present for evaluation without any symptoms at all.3

|

| The optic disc edema seen in these fundus images is a telltale sign of the neuro-ophthlamic condition papilledema. Click image to enlarge. |

Ophthalmoscopy

On dilated examination, patients with increased ICP will commonly present with optic disc edema. This is usually a bilateral and symmetric finding; however, asymmetric or unilateral optic disc edema occurs in roughly 10% of papilledema cases.1 Optic disc edema can be graded based upon its severity, which includes factors such as extent of clock-hour involvement and vessel obscuration by the edematous nerve fiber layer.

Patients with disc edema secondary to increased intracranial pressure will not exhibit a spontaneous venous pulsation. While roughly 10% of the healthy population does not have a spontaneous venous pulsation, the presence of one is an important finding and eliminates papilledema from the differential diagnosis.3 Additional clinical findings with papilledema may include a visual field defect, most commonly in the form of an enlarged blind spot.3 These patients may also report photophobia or eye pain.3

It’s the clinician’s job to differentiate true optic disc edema from optic disc anomalies, such as tilted disc syndrome and optic disc drusen, to avoid unnecessary costly work-up. This can be accomplished using diagnostic tools, including optical coherence tomography and fluorescein angiography, to rule out true swelling of the optic nerve. Also, A- and B-scan ultrasonography can be used to distinguish optic disc edema from optic disc anomalies. More specifically, a 30-degree test can be performed in which the optic nerve width is measured in primary gaze and in lateral gaze. If the optic nerve width is reduced by more than 10% with 30 degrees of lateral gaze, it is indicative of true optic disc edema.4 The lateral gaze position causes stretching of the optic nerve and increases the distribution area for the fluid surrounding the nerve, which results in a decrease in optic nerve width.4

Diagnosis

Bilateral optic disc edema should always be treated as an emergent situation. Clinicians must rule out urgent causes of increased ICP, including mass and hemorrhage. Comprehensive work-up should begin with same-day magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and orbits, with and without contrast material. If MRI is not readily available, then a computer tomography (CT) scan with contrast dye should be obtained.

If MRI findings are normal, one should consider a magnetic resonance venography (MRV) to rule out venous sinus thrombosis. With unremarkable findings, a lumbar puncture should be the next step in diagnosis.3,5 This should always be performed after an MRI or CT scan, due to the risk of herniation, specifically with Chiari I malformation.4 A lumbar puncture is typically performed while the patient is lying on their side.2 An opening pressure of greater than 250mm CSF in adults is diagnostic for increased ICP. Additionally, the CSF contents should be examined to rule out infectious or inflammatory causes of disc edema.3

If neuroimaging and lumbar puncture results are normal, pursue a laboratory work-up to rule out other potential causes of bilateral optic disc edema. This laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential, platelet count, HbA1C, ESR, CRP, ANA, RF, ACE, Lyme titer, serum folate and serum B12.6 Also, measure blood pressure in all cases of bilateral disc edema, to exclude malignant hypertension as the underlying cause.3

If increased ICP is noted without any other abnormalities following comprehensive investigation, a diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension can be made. Be aware that several drugs are associated with idiopathic intracranial hypertension, including tetracyclines, oral contraceptives and vitamin A analogs.2

Treatment Options

Papilledema should be managed by treating the primary source of the increase in ICP. If the elevation in pressure is found to be idiopathic, or is not fully resolved with treatment of the causative mass or vascular abnormality, additional management options should be considered. First, in the case of idiopathic intracranial hypertension, or pseudotumor cerebri, weight loss should be an initial therapeutic consideration. Research shows a 6% reduction in body weight may contribute to resolution of papilledema. Additionally, acetazolamide, an oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, may be used to treat increased ICP. Standard dosage of acetazolamide in the treatment of elevated intracranial pressure is 500mg BID, with the option of increasing to a total dosage of 4g daily, if necessary.3

Further, options that may be considered for patients who are intolerant or unresponsive to acetazolamide treatment include loop diuretics, serial lumbar puncture, optic nerve sheath fenestration and shunting procedures.1,3 For headache management, topiramate may be added to the therapeutic regimen. Topiramate has been shown to induce mild weight loss, which may contribute to improvement in papilledema as well.1

A key responsibility in addressing these patients is to differentiate true optic disc edema from other, less emergent optic disc abnormalities. When papilledema is suspected, immediate referral should be made for neuroimaging and potential lumbar puncture, to rule out emergent causes of bilateral optic disc edema. Rapid diagnosis and evaluation is essential in cases of papilledema to save the patient’s vision and, potentially, their life.

Dr. Thompson is a consultative optometrist at SouthEast Eye Specialists in Chattanooga, Tenn.

1. Rigi M, Almarzouqi S, Morgan M, Lee A. Papilledema: epidemiology, etiology, and clinical management. Eye and Brain. 2015 Aug;7:47-57. |