|

Viruses are ubiquitous pathogens that can have widespread effects on the body, including virtually all ocular tissues. Some patients are particularly susceptible to certain viruses, such as herpes. Humans are the primary host for eight herpes viruses: herpes simplex 1, herpes simplex 2, varicella-zoster, Epstein-Barr, Human herpesvirus-6, Human herpesvirus-7, Kaposi’s sarcoma herpes virus and cytomegalovirus (CMV), which is the cause of several diseases.1,2 CMV is a large-enveloped, double-stranded member of the Herpesviridae family of DNA viruses.

CMV gained recognition during the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic for causing infectious retinitis in susceptible patients. More recently, it has emerged as a cause of ocular and systemic sequelae in immunocompetent patients.3,4

|

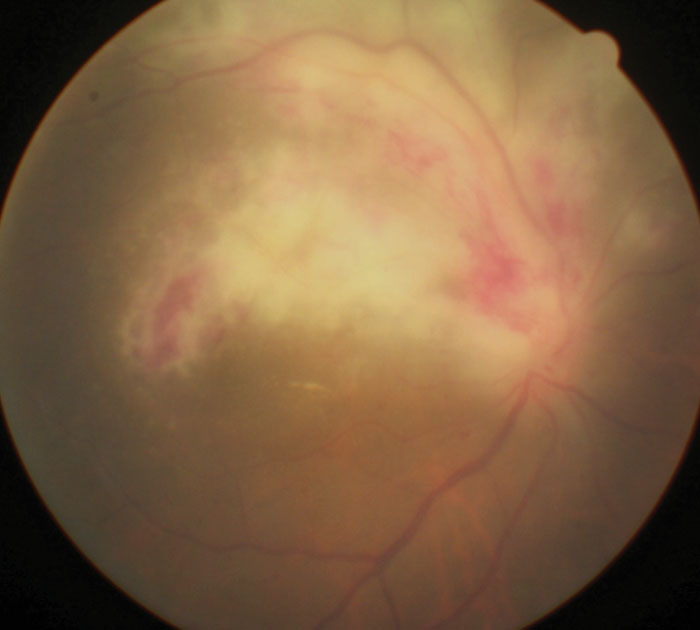

| This patient diagnosed with AIDS presented with signs of CMV retinitis. |

HIV Opens the Door

AIDS, caused by the blood-borne retrovirus HIV, is characterized by profound immunosuppression that leads to opportunistic infections, including CMV. AIDS may also lead to secondary neoplasms, neurological manifestations and death.1,2 A person’s CD4+ T-cell count reliably reflects their current risk of acquiring opportunistic infections.2

Approximately 80% of HIV-infected patients will be treated for an HIV-associated eye disorder.3 Posterior segment findings may include an HIV-associated retinopathy/vasculopathy and a number of opportunistic infections of the retina and choroid.3

Infection and Consequences

CMV is transmitted from person to person by breast milk, saliva or sexual contact. It can also be transmitted by organ transplantation.2,3 CMV infects 50% to 85% of adults in the United States by age 40 and is also the virus most frequently transmitted to a child before birth.

Like others in its viral family, CMV has a characteristic ability to remain dormant in the body over a long period. Initial infection, which may have few or even no symptoms, is followed by a prolonged period of infection during which the virus resides in cells without causing detectable damage or clinical illness. Severe impairment of the immune system by medication or disease can reactivate the virus from its dormant or latent state.1-3

Table 1. Common CMV Manifestations1-4 | |

| System | Condition |

| Gastrointestinal |

|

| Respiratory |

|

| Hematological/Cardiovascular |

|

| Neurological |

|

CMV disease can present with a wide range of manifestations, with colitis being the most common (Table 1).1-4 CMV infection is a particular concern for certain patient populations because of the risk of infection to unborn babies, people who work with children and immunodeficient individuals, such as transplant recipients, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and those living with HIV.

CMV retinitis occurs in patients who have failed to generate a primary T-cell response against the virus or who are carriers of CMV but whose previously effective CMV-specific T-cell response has decreased due to disease or immunosuppressive treatment.3

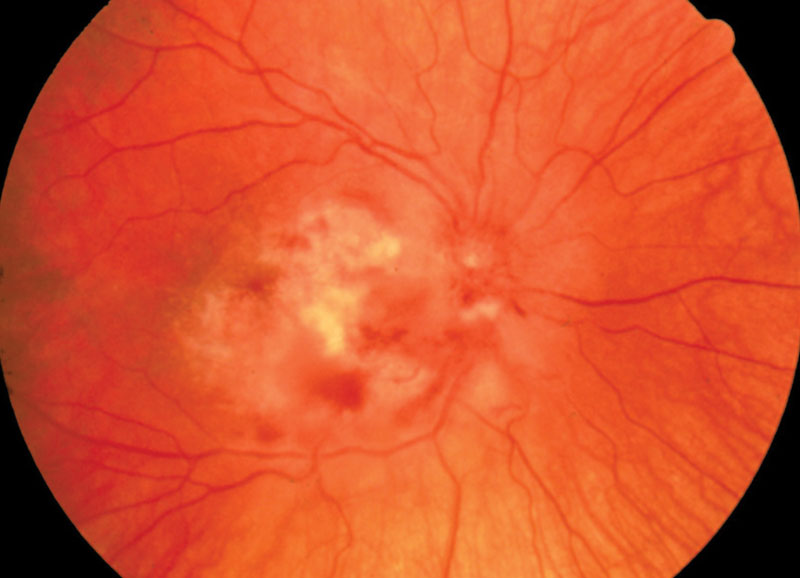

CMV produces a characteristic ophthalmoscopic appearance of a pale, necrotic retina, often with focal areas of hemorrhage in a sectoral distribution spreading along vascular arcades. When retinitis is inactive following anti-CMV treatment, the retina remains thin and atrophic with clumping of the pigment epithelium.3 Visual function loss is mainly due to direct extension of the retinitis to the macula or optic nerve head, or retinal detachment.

The diagnosis of CMV retinitis can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction amplification of viral DNA in the aqueous.2,3

Hostile TakeoverA virus exists as a protein coat, or capsid, that surrounds either DNA or RNA, which codes for the virus elements.1 A virus cannot reproduce by itself; instead, it inserts its genetic material into the host cell and takes over its functions. In DNA viruses, such as herpes simplex, the viral genetic material is replicated, transcribed (producing mRNA) and translated (creating proteins from the mRNA) when it enters a cell. By this process, the host cell uses the genetic instructions in the virus to make more viruses.1,2 |

Treatment Options

Intravenous administration of the antiviral drugs ganciclovir and foscarnet has modest penetration into the vitreous compared with direct intravitreal injection.3 In randomized trials of HIV-associated CMV retinitis, a ganciclovir implant was consistently superior to intravenous ganciclovir in preventing progression.3,4

Combination anti-HIV treatment effectively controls HIV replication and restores the number and function of CD4+ T-cells, giving most patients a near normal life expectancy. In countries where effective treatment is available, the incidence of HIV-associated CMV retinitis has decreased substantially. It should be noted that in up to 40% of HIV-infected patients with CMV retinitis, initiation of anti-HIV treatment leads to an immune recovery uveitis, which may include anterior uveitis, cataract, posterior uveitis, cystoid macular edema, optic disc edema and epiretinal membrane formation. Treatment with corticosteroids is often necessary in these cases.3,4

|

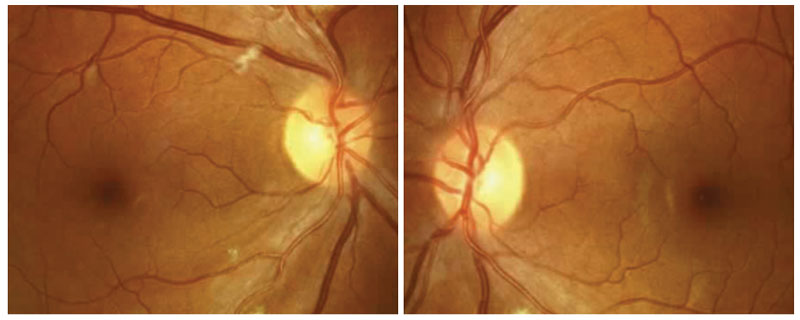

HIV retinopathy may present with cotton-wool spots, hemes and other vascular changes. |

CMV in the Immunocompetent

Unfortunately, the incidence of CMV disease in immunocompetent adults appears to be greater than previously thought, possibly due to immune dysfunction related to comorbidities, such as diabetes or kidney disease. CMV infection in healthy adults is usually asymptomatic or causes a mild mononucleosis-like syndrome. However, over 380 published case reports document instances of severe, tissue-invasive CMV infection in immunocompetent adults.4

|

This patient has CMV retinitis with optic disc edema. |

Similar to CMV disease in immunocompromised patients, these cases show a wide range of manifestations, including colitis, vascular thrombosis, pneumonia and myocarditis.3,4 CMV has emerged as a cause of kerato-uveitis, anterior uveitis and retinitis in immunocompetent patients, the complications of which are associated with significant morbidity.5,6 Along with the common ophthalmic therapies, targeted antiviral therapy with ganciclovir or valganciclovir is appropriate for severe CMV ocular disease in immunocompetent adults.4,5

CMV can present with a wide range of ophthalmic manifestations and causes significant morbidity and mortality in neonates and severely immunocompromised adults. However, CMV disease in immunocompetent adults also has been increasingly reported in recent literature, and optometrists should add it to the list of suspected causes of kerato-uveitis, anterior uveitis and retinitis in healthy patients.

| 1. Knipe DM, Howley PM, et al. Fields’ Virology. 5th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. 2. Carter J, Saunders V. Virology: Principles and Applications. 2013:1-65. 3. Carmichael A. Cytomegalovirus and the eye. Eye (Lond). 2011;26(2):237-40. 4. Lancini D, Faddy HM, Flower R, Hogan C. Cytomegalovirus disease in immunocompetent adults. Med J Aust. 2014;201(10):578-80. 5. van Boxtel LA, van der Lelij A, van der Meer J, Los LI. Cytomegalovirus as a cause of anterior uveitis in immunocompetent patients. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1358-62. 6. Koizumi N, Suzuki T, Uno T, et al. CMV as an etiologic factor in corneal endotheliitis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:292-7. |